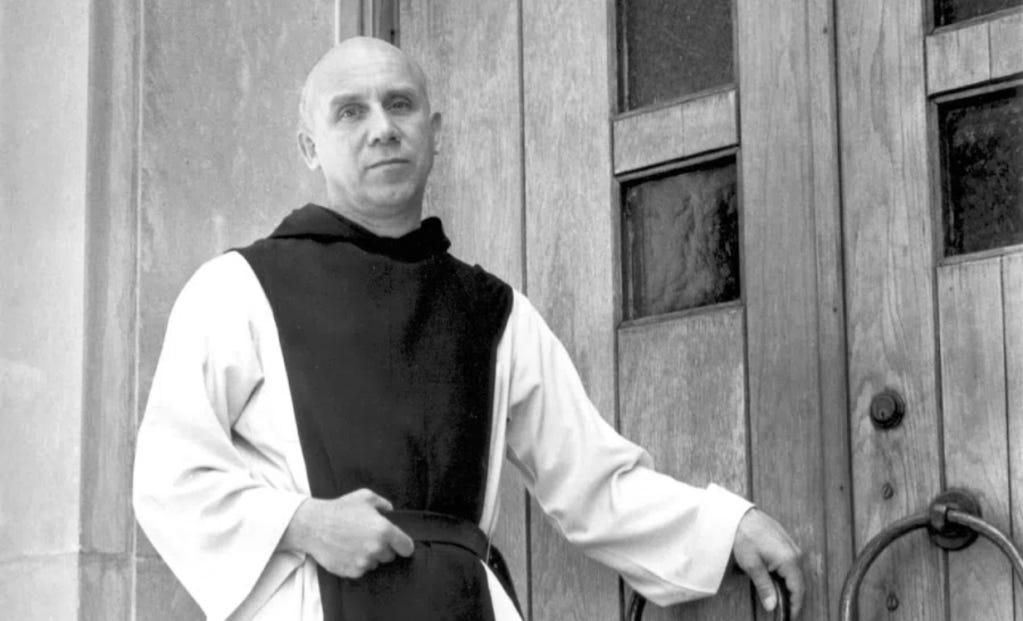

This March 30, 1962 letter from Thomas Merton to Etta Gullick is a window into one of the most charged moments in Merton’s life—a time when his monastic vocation, mystical theology, and political conscience collided. He was writing from the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, a cloistered place increasingly too small for his moral vision. What this letter shows is not just the mind of a monk, but the spirit of a man trying to hold faith and conscience together in the nuclear age.

“They have the wind up and are moved to vehement malevolence…”

Merton begins with a reflection on Julian of Norwich, the medieval English mystic, and her relevance to the Dark Night of the Soul—that deep, often terrifying experience of spiritual desolation described by 16th century Spanish priest and Carmelite friar St. John of the Cross. But Merton does something interesting here: he moves beyond the abstraction of classic mystical “experience” and anchors it in the Paschal movement—passing with Christ through death out of this world to the Father. He rejects neat categories. He insists that the truest spiritual transformation defies systematization. It is incomprehensible, because it moves with the mystery of God, not the logic of humans.

That same discomfort with simplification spills into the political. When Etta Gullick asks if he’s unpopular for writing about peace, he answers plainly: “Yes and no.” The real answer, of course, is yes. And it’s the kind of yes that comes with cost.

“Certainly criticized vigorously and unfairly… vehemence… malevolence…”

These are strong words from a monk, and not casual ones. By 1962, Merton had begun publishing essays and private letters that directly criticized nuclear armament, American Cold War policies, and the Church’s silence. For this, he faced pressure from both his abbot and American bishops, many of whom wanted him to remain silent, obedient, and apolitical.

But silence, for Merton, had become its own sin. He wasn’t a protester in the street. He was something more dangerous: a voice within the institution, calling it to conscience. His tone in this letter is not panicked, but weary. Still resolute.

“People have not the time to really think about this issue.”

That line may be the most damning. He’s not accusing them of malice—but of mental laziness, fear, and moral inattention. In his view, the nuclear bomb didn’t just threaten life; it threatened thought, conscience, and the capacity for authentic Christian witness.

He mentions E. I. Watkin, a British Catholic philosopher whose 1957 book The Catholic Centre criticized the Church’s failure to speak against nuclear weapons. Merton aligns himself with Watkin, with Pax Christi in England, and with the idea of forming a Pax movement in the U.S.—even though, as he says wryly, “of course too late to mean anything.”

That last line aches. It’s sarcastic, yes—but also resigned. Merton wants peace, not just politically, but spiritually. He wants the Body of Christ to act like one. But the world feels hurtling, indifferent, doomed to its illusions.

Why This Letter Matters:

It reveals a mystic as a moral realist. Merton blends the contemplative and the political, showing that prayer and action are not opposites but obligations.

It diagnoses the disease of indifference. He doesn’t just rail against nuclear weapons—he critiques the shallowness of public imagination and the Church’s complicity in it.

It refuses simplification. Whether discussing mystical experience or geopolitics, Merton resists categories and easy answers. That makes him deeply relevant today.

It marks a turning point. This letter is part of the sequence that led to Merton’s growing estrangement from ecclesial approval and toward a broader, riskier kind of witness.

It connects contemplation with courage. Merton’s authority doesn’t come from outrage but from inner clarity. That’s why the letter still rings true: it’s the sound of a man choosing integrity over safety.

In a time when many faith voices fall silent on public matters (or take very strange stances and allies), Merton’s courage continues to challenge. He didn’t shout, but he didn’t flinch. This letter asks us: What are we too afraid—or too distracted—to think about? And what would it cost to speak, even gently, against the easy consensus of our time?

This letter came from Thomas Merton: A Life in Letters, The Essential Collection, edited by William H. Shannon and Christine M. Bochen (HarperOne), 2008.